This post includes contributions by Jon Hanford, Nicole Hentrich, Meesha Meksin, Nikolas Nyby, and Marc Raymond. This reflects the collaborative nature of the project.

Virtual and augmented reality (VR and AR), 360-degree video, and other immersive technologies have been heralded as the new frontier of education for many years. Perhaps spurred by the pandemic and the need to come together across geographic distance, the interest and desire to invest heavily in these technologies has only intensified.

The effective use of these technologies, however, has remained elusive in many educational contexts. This is in part because of an over-emphasis on the technology itself, rather than the student learning experience. In addition, many of the attempts to incorporate these technologies into the classroom have come from corporate promotions that seek to “retrofit” proprietary technologies for educational purposes. Frustration from these attempts has led many to question the efficacy of these technologies for education with some, such as Malcolm Burt, writing for the Times Higher Education, saying that they have ultimately failed. While Burt writes about the difficulties of educating students on the use of VR, rather than the use of VR to serve other educational goals, the overall point is still well taken: VR, AR, and 360-degree video have not been widely adopted in college classrooms.

We offer an alternative approach that prioritizes student learning and course goals. Of course, this is not a new approach in course development but one that is often lacking when technology, whether specifically designed for education or not, is used. That approach is a backward design framework. Start with the “so what” question. What is it we want students to be able to do or know? From there, how can we achieve this goal and is technology part of that answer? It ultimately may not be, and that’s ok too. If it is, then we can think about how we develop and implement it.

We approached the Greek Streets Project in this manner. Intended as part of the Modern Greek language sequence within the Department of Classics, Greek Streets uses street art in Athens to help with language instruction and cultural exploration. Faculty member and program director Dr. Nikolas Kakkoufa already used images of graffiti in his classes and had found them helpful teaching tools but they lacked the place-based aspect of full immersion. Further, some students in the class had the means to travel to Greece or to study abroad there, but others did not and that created a lack of common experience and a gap in cultural literacy.

Rather than starting with unrealistic expectations, we instead heeded Malcolm Burt’s call for educators to “juggle their justifiably heightened expectations of this technology’s future with more modest applications in the present.”

We took ideas from VR and applied them to an accessible web experience in our Greek Streets collaboration with Kakkoufa. We integrated a series of 360-degree videos into a website that centers on locations in Athens, showing the graffiti and street life that you could otherwise only experience in person.

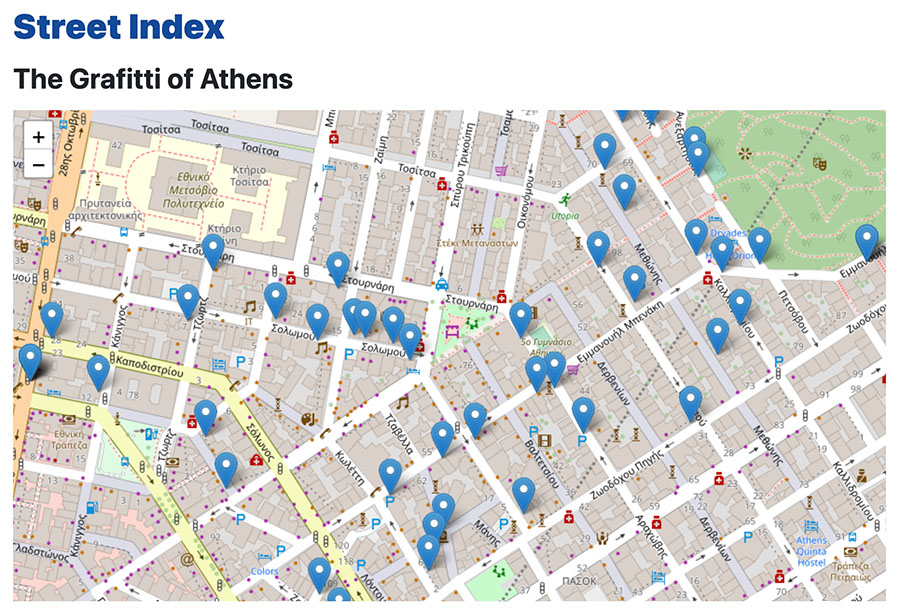

A map of Athens showing the locations of 360-degree videos captured for this project.

From a video production point of view, immersive media presents unique constraints and challenges. The rules and established norms of traditional shooting and editing don’t apply; the viewer is their own cinematographer, and their consumption of the media is more active and less passive. Since the viewer determines–to an extent–their own path and sightlines, pre-production techniques like shot-listing and storyboarding are no longer sufficient planning tools.

To approach the production of this project in a purposeful way required starting from square one. Immersive media like VR can sometimes be reduced to simply being a novel experience. It can fail to provide a cogent answer to the question: how does this technology support student learning in the course? By starting with learning objectives we arrived at a very real answer, and the overall purpose itself informed the production process.

Unlike photographs, paintings, or the moving image, a work of street art will only ever exist in one place. Its location, surface, and surroundings are part of the work in an inexorable way. Even if one were to carefully disassemble a wall and reassemble it in a museum, it would no longer be the same work. The charge to the production therefore became to provide the viewer with as much of the total experience of encountering the work in situ as possible. This also tied into one of the learning objectives of the course which was textual analysis that attended to site-specific context clues.

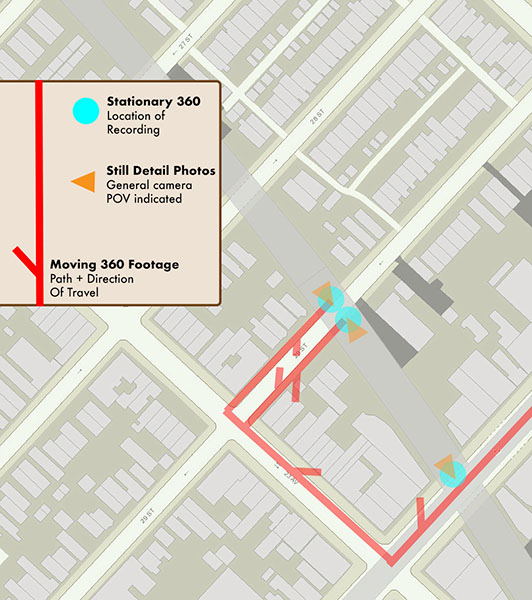

This meant not only capturing the work in its surroundings, but capturing the surroundings themselves and the approach to any given location. Immersive video would be recorded not only from a static position in front of the work, but from a moving perspective one might have as you walk up to it. An unanswered question was how to communicate the logistics of such capture to remote videographers located in Greece when the traditional methods of storyboards and shot lists did not apply.

In lieu of transporting CTL production staff to Greece to plan this out, a serviceable substitute was found in some street murals in the heavily Greek-American neighborhood of Astoria, Queens. We carried out test recordings, and from those tests a visual language for communicating capture plans and locations was created, then shared with the remote partners.

A map used for planning out test 360-video recordings in Astoria, Queens.

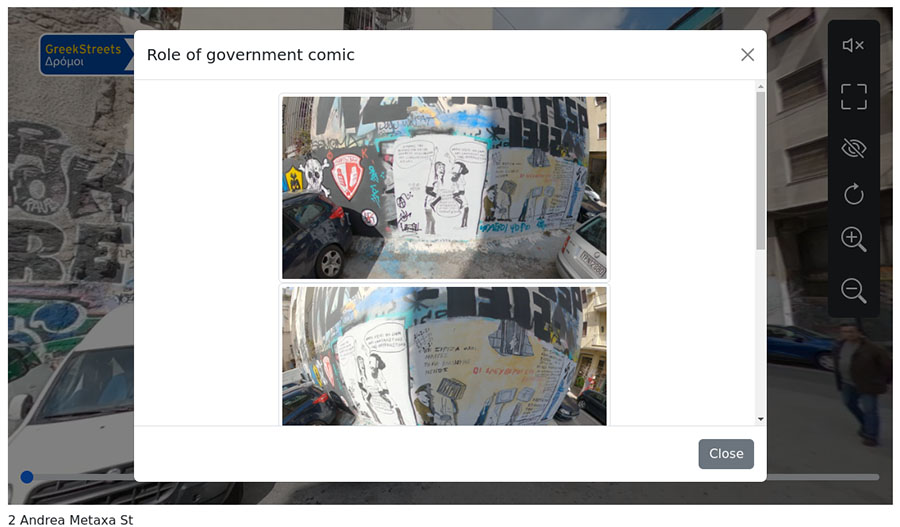

While we worked on production, we explored ways for the students to interact with the videos. We used a JavaScript library called A-Frame to make our 3D world and put our 360-degree videos inside it. By pointing out areas of interest in the video, the viewer is brought into a zoomed-in view of the work in question, with descriptive text. In this way, the streets of Athens turn into an immersive art gallery that can be explored by students either through a guided experience or a more discoverable one. In doing so students can encounter works to translate, artists to research, and be exposed to socio-cultural phenomena without setting foot in Athens.

A screen-capture of the 360 video-based virtual environment that allows users to explore and interact with the streets of Athens.

A detail view showing the interaction with high-resolution images embedded within a 360-degree video. This example focuses on a politically satirical comic within a densely packed wall of graffiti.

No doubt, we could extend our use case to include a full VR headset, but for our educational goals at hand, that wasn’t necessary. Hardware requirements such as this are also an accessibility issue in terms of both disability and resources. When investing in new technologies, it is important to be purposeful and intentional about what is being built. Are we making something just because it’s new and trendy, or are we actually fulfilling a real pedagogical need?

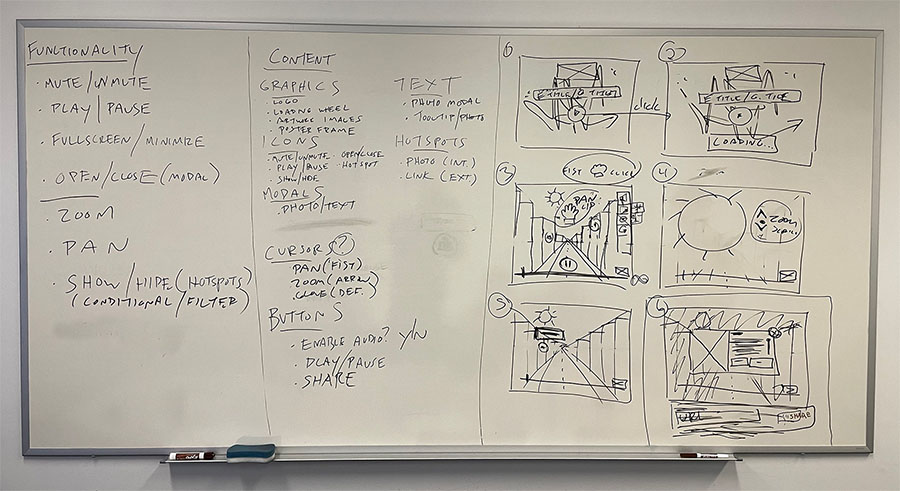

We laid out a user-experience design plan for Kakkoufa’s students that supported proven, pedagogical strategies first instead of being led by glossy and unrealistic VR ideals and proprietary hardware. Navigation, information, and interface design requirements prioritized current two-dimensional web conventions in order to ensure simplicity, intuition, and accessibility in a three-dimensional virtual space.

In order to create the navigation, interface, and information design of the prototype, the team had to first define the requirements of the functional design and content during an in-depth white-boarding session.

Ultimately this project has been an experience in creative problem solving and a pilot for the purposeful use of 360-degree video in a course context. By using a backward design approach as well as being tech-agnostic from the beginning we were able to explore all available options. This put the technology in the service of the learning goals for the course rather than the technology determining use cases.

Printed from: https://compiled.ctl.columbia.edu/articles/360-video-edu-context/